“There’s the Donald Trump that you see on television and who gets out in front of big audiences, and there’s the Donald Trump behind the scenes. They’re not the same person. One’s very much an entertainer, and one is actually a thinking individual. [As voters] begin to see the real individual there, I think we’re going to be comforted as a nation.” - Dr. Ben Carson

Speaking from personal experience, I’d say Carson has a point. Several years ago, when Trump Plaza in New Rochelle topped-off to become the tallest structure in Westchester County, the future GOP front-runner came to town to celebrate the occasion. As mayor, I joined him for an elevator ride to the top floor of the still-unfinished building and then, later, for a short walk to a local restaurant with other community leaders.

I had never been a fan of Trump’s flashy style and expected to find the man repellent in person, but, in fact, he was quite appealing: pleasantly soft-spoken, warm, friendly, an engaging storyteller, and, most surprisingly, a thoughtful listener. I couldn’t help myself - I liked him.

And I am not alone. Sheldon Adelson and Clay Aiken, two people who are unlikely to have much else in common, have both described Trump as “very charming.” Tom Brady, who can probably have his pick of social relationships, has “always enjoyed the company” of his “good friend” Trump. Even Trump’s former butler calls him “entirely a nice guy.”

True, Trump’s charms have been mainly under wraps in the snarling arena of the Republican primary campaign. But if, as seems likely, Trump advances to the general election, with a new, wider audience to win over, then his gentler qualities may be put to better use.

Will many Americans be, as Carson puts it, “comforted?” It is quite possible.

So this seems an important moment to remember one of history’s vital, but underappreciated, lessons: monsters can be charming.

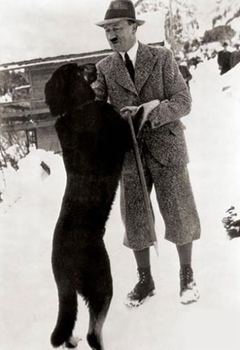

Search the Internet for “Adolf Hitler with dogs,” and you will find some odd little films of the Fuehrer at his alpine retreat. He looks every bit the kindly country gentleman, as he dotes lovingly on his German shepherd and watches puppies skitter around the terrace.

To the modern viewer, these films are disorienting. Knowing today the colossal scale of Hitler’s monstrosity, one expects it to overspill every aspect of his persona, to be horribly visible from all angles. We picture Hitler in a perpetual rage, striding about the Reich Chancellery, glowering and declaiming at henchmen. He seems the kind to kick a dog, not pet it.

But no. And it’s not just the happy afternoons in the Berchtesgaden with the dogs. Here is Hitler on the Berlin social circuit, being gushed about for his dazzling wit. There he is laying a gentle hand on a sweet pig-tailed girl, who beams back at him adoringly. The incongruity of it all is difficult to process... which makes the lesson hard to absorb.

And Hitler was hardly unique among historical figures in presenting such confusing incongruities.

Stalin composed poetry and contributed a lovely singing voice to his church choir, before going on to murder millions of his countrymen and enslave the rest.

The Shah of Iran cut a dashing figure in his finely-tailored western suits, entertaining celebrities amid strutting peacocks and flowing champagne. Meanwhile, his secret police, dressed more somberly, entertained dissidents with electrical implements and fingernail extractions.

Nero delighted his subjects by competing personally in athletic competitions and appearing on stage as an actor, when he wasn’t otherwise occupied beating his pregnant wife to death and then mutilating her replacement.

There is also a distinct sub-species of strongman-clown. Idi Amin with his overstuffed, sweat-coated comic bluster. Kim Jong-Il with his strange hair, platform shoes, and peculiar Hollywood obsessions. The first could have starred in his own sitcom, the second was the real-life inspiration for a real-life (albeit puppet-acted) comedy film. It is easy to laugh, until you remember the thuggery, hijackings, nuclear tests, and mass starvation.

All these plays against type, these incongruities, are unsettling precisely because we expect danger to be easier to spot and harder to disguise, because we want monsters to present themselves helpfully in horns and cloven feet and are surprised when sometimes they don’t.

But monsters, it seems, can be nice to children. They can be kind to animals. They can be loyal to friends. They can be comically oafish or gracefully elegant, sharp dressers and talented writers, and many other things that are “comforting,” or at least unthreatening.

They are still monsters.

Comparing any contemporary American political figure to Hitler can be extravagantly unfair. A disclaimer is required: Donald Trump gives no indication of being a would-be mass murderer or world conqueror (sadly, torturer and war criminal cannot be ruled out, given his explicitly supportive statements on these topics.) It’s not even clear that Trump is a real bigot - his pronouncements have the air of opportunistic demagoguery more than of genuine personal prejudice. Is Trump a crypto-fascist? Who knows? It seems just as likely that he has no coherent political philosophy whatsoever, beyond self-aggrandizement.

But that’s where the disclaimer ends, because whatever Trump’s inner thoughts, Trump’s candidacy, his message, is fascist - fascist to the core.

How else can one label the simmering undercurrent of violence, the mocking contempt for norms of civil discourse, the drumbeat of demonization, the simplistic and counterfactual mythologies, the cult of personality, the elevation of strength above all other virtues?

The message is all-too-familiar:

Trust in me and we shall be great once more. The traitors in our midst and the hordes at our gate shall be swept away. What they took with their clever tongues and grasping hands shall be ours again. For I am a strong man with a hard fist, and I am your champion.

No matter the language, setting, or era, the essence of this appeal is ever the same. And when it moves a people to action, it always - always - ends in tragedy.

A campaign won on such a basis would be profoundly, disastrously harmful to our democracy, even if the policies of the subsequent presidency proved to be innocuous. The validation of the message is, by itself, enough to do catastrophic damage to the strength and durability of our political institutions and culture. Like an illness that wipes out our resistance, it would leave us more vulnerable to the next infection, and the next after that. In this sense, Donald Trump’s success presents the most serious and frightening internal challenge that American democracy has ever faced.

Yet Trump’s incongruities, like those of others in history, can conceal the full ominous scale of our danger. The problem is not that Ben Carson may be wrong in his observations about a second “cerebral” Trump with the capacity to comfort and charm; the problem is that Carson is probably right.

And even if not, there is already at work an equally potent numbing agent for our threat instincts: Trump’s sheer outrageousness. Those who prove resistant to his charms - who are mortified by his antics - still tend to see Trump as an embarrassment more than a menace, as a clown more than a danger. How can we really be frightened by someone who hawks wines and steaks during a victory speech, as though CNN were QVC? By a guy who cheerfully debates the hotness of various women with Howard Stern? By a performer who issues a trademark catchphrase on The Apprentice and assures us that his hands and other parts are amply-sized? A laughingstock yes, and that’s bad enough, but a true threat to our democracy? It doesn’t add up.

Until we remember that Hitler loved dogs.